In-Person Family Time During the COVID-19 Pandemic

Family Time and Washington’s Pandemic Response to Date

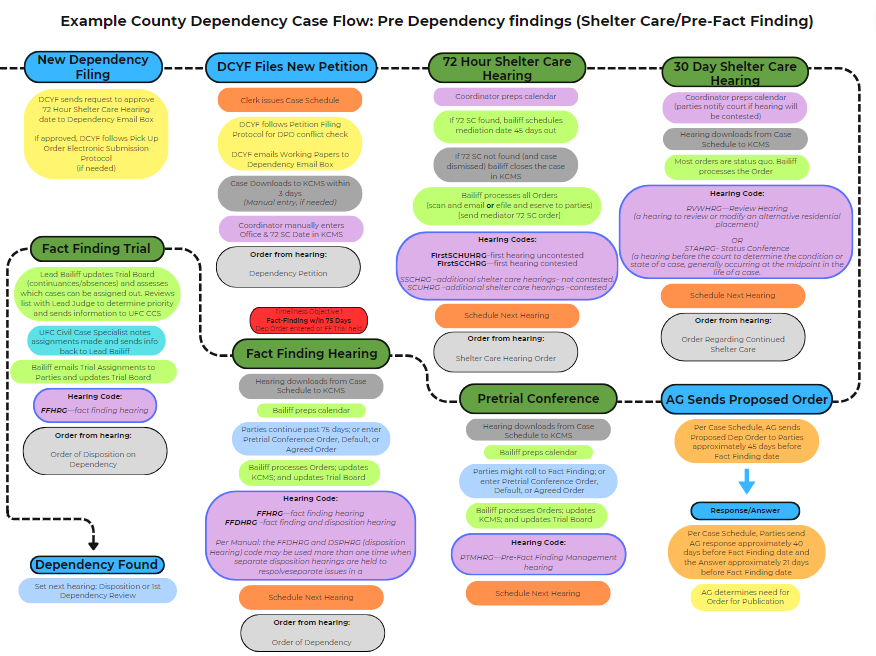

In response to the COVID-19 health crisis, Governor Inslee signed Proclamation 20-33 on March 26, 2020, waiving RCW 13.34.136 family time visit requirements that DCYF provide the “maximum” contact “possible” and permitting the Department to limit, but not entirely suspend, visits without court approval. The original proclamation cited concerns that the foster care system could be destabilized if caregivers and group home providers refused placement of children because they feared exposure to the virus as a result of in-person family time.

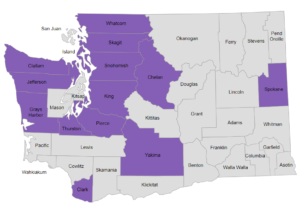

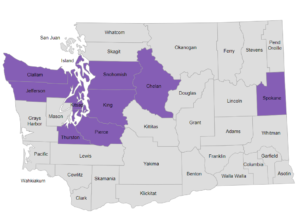

Since March, DCYF has requested multiple extensions of the governor’s proclamation, asserting the need for flexibility to ensure safety and to allow time for DCYF and providers to return to in-person visits with cleaning and safety protocols in place. The current extension, Proclamation 20-33.8, is scheduled to expire on August 31, 2020, when DCYF’s stated goal is to return to in-person visits to the extent safely possible, with remote visits still an option (see attached DCYF Proclamation 20-33 Extension Clarification Letter: Proclamation 20.33 extention clarity letter 08042020). DCYF leadership has maintained that the proclamation does not suspend or prevent in-person visits. However, local offices have interpreted the proclamation differently, leading to confusion and the inconsistent provision of in-person visits across the state.

In early April, the Washington Supreme Court issued Order No. 25700-B-614, which provides guidance to courts for ruling on motions seeking in-person visits between children and their parents or siblings under the proclamation. The justices acknowledged that virtual visitation could serve as a temporary solution to preserving family connections, but it will not be sufficient in some cases because the disruption/denial of in-person contact will not be in the best interest of the child. The order encourages courts to hear these motions on an emergency basis; outlines 11 specific factors courts should consider; and requires that court orders providing for in-person visits “mandate the specific health, safety and welfare protocols that must be followed.”

Ensuring In-Person Visits and Safety in an Uncertain Time

“As we pull out all the stops to prevent broader infection, we must also remain vigilant in caring proactively for those who are especially vulnerable to the threat and consequences of social isolation.”

Jack P. Shonkoff, M.D.

Harvard University Center on the Developing Child[1]

In the face of uncertainty about the pandemic’s course and the state’s response, it is important that courts consider the detrimental impact that limited or no in-person contact has on children and their parents. Under normal circumstances, children experience removal and placement into foster or group care as a significant traumatic experience, often resulting in feelings of ambiguous loss.[2] Experts note that disruptions in the parent-child relationship may “provoke fear and anxiety in a child and diminish his or her sense of stability and self.”[3] Presently, the trauma of removal is compounded by the more universal upheaval of pandemic-induced school closures and the stress of living under quarantine and social distancing requirements. Childhood health experts are deeply concerned that the crisis will have serious consequences for children and youth all over the world, delaying their cognitive, emotional and social development.[4]

Predictable and consistent family time visits are critically important for children who have experienced trauma, and they favorably impact case outcomes. Parents play a crucial role in their child’s development, buffering the child’s stress by helping them to make sense of their experiences and feel safe in the aftermath of traumatic events.[5] Children and youth who participate in regular visits with parents exhibit more positive outcomes than peers who participate in fewer or less regular visits, including lower levels of depression and better adjustment to placement.[6] Visits also support parents’ emotional well-being and provide motivation to help them fulfill the requirements of their case plans.[7] Finally, research indicates that regular, meaningful family time expedites permanency and increases the likelihood of reunification.[8]

While remote visits have been widely implemented in Washington during the first four months of the pandemic, it is important to recognize that video chat sessions are not an adequate substitute for in-person contact, particularly for young children. Children need to know that their parent is available and cares for them.[9] Research has shown that, the younger the child and the longer the period of uncertainty and separation from the primary caregiver, the greater the risk of emotional and developmental harm to the child.[10] Very young children require close physical proximity and frequent, repeated interactions with a parent in order to develop an attachment relationship.[11] Because their capacity to remember people and experiences is limited, infants cannot hold a parent in mind for long periods of time between contacts.[12]

To support resumption of in-person family time, DCYF consulted with the Department of Health to create health guidance and protocols to minimize the risk of virus transmission during a visit. The protocols include screening questions for parents and caregivers; safety protocols that must be observed during a visit, including hand washing, mask wearing (for those over the age of 2) and social distancing; and cleaning guidelines for transportation and visit locations. To ensure all parties understand the requirements that apply to them, DCYF developed separate guidance documents for everyone involved in providing and participating in visits.

Family Time In-Person Visits Guidance Protocol Provider

Family Time In-Person Visits Guidance DCYF Staff

Family Time In-Person Visits Guidance Parents

Family Time In-Person Visits Guidance Foster Parent and Kinship caregivers

Recognizing that some places where families used to visit are closed under the Safe Start Washington Plan, DCYF and visitation providers have developed a list of currently available locations in every region of the state (see attached Provider Resource List: PROVIDER RESOURCE LIST 08032020). The locations include outdoor spaces, such as parks and sports fields, as well as libraries, community centers and other indoor public places. DCYF is also arranging for visits to occur at their field offices.

If caregivers have concerns or express resistance to in-person family time contact, DCYF has a process in place to engage caregivers, parents, youth, attorneys, advocates and others in creating and revising the Family Time Plan for each case. Caregivers may need help understanding all of the health and safety precautions required, as well as the serious negative impacts on children of not having contact with their parents and siblings. DCYF Policy 4254 Family Time and Sibling and Relative Visits, requires that each family have a written Family Time Plan that outlines the level of supervision, location, frequency, duration, transportation, and any other necessary details. Family Time Plans are supposed to be reviewed at all shared planning meetings and during monthly supervisory case reviews. The court should receive a copy of each family’s plan and be informed of changes to the plan.

Virtual visits, which are commonplace now, should be utilized in addition to in-person contact. The Department’s policy requires that visits be face-to-face but also encourages supplementing visits with telephone, electronic and video contact. Family Time plans should include regular video or text contact to help children maintain connections with parents and siblings between in-person visits. Especially with the added stress of COVID-19, regular virtual connection with parents (such as good night calls or text check-ins) can provide predictability and reduce anxiety for children in care.

More information regarding virtual visits and returning to in-person visits is available in a series of recorded webinars on the Court Improvement Training Academy (CITA) website:

- CITA Webinars #1 and #2: Resources for Family Time in the COVID-19 Era

- CITA Webinar #3: Support and Coaching for Virtual Family Time Visits

- CITA Webinar #4: Moving to In-Person Visits During COVID-19: Dispelling Myths, Fears and Assumptions

[1] Jack Shonkoff, “Stress, Resilience, and the Role of Science: Responding to the Coronavirus Pandemic” (March 20, 2020), available at: https://developingchild.harvard.edu/stress-resilience-and-the-role-of-science-responding-to-the-coronavirus-pandemic/

[2] Vivek Sankaran. “A Cure Worse Than the Disease? The Impact of Removal on Children and Their Families.” Christopher Church and Monique Mitchell, co-authors. Marq. L. Rev. 102, no. 4 (2019): 1163-94.

Lee, Robert E. and Whiting, Jason B. (2007) ‘Foster Children’s Expressions of Ambiguous Loss’, The American Journal of Family Therapy, 35:5, 417 – 428 http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/01926180601057499

[3] Nicholson v. Williams, 203 F. Supp. 2d, 153, 199 (E.D.N.Y 2002) (testimony of expert witness Dr. Peter Wolf).

[4] David Robson, “How Covid-19 is changing the world’s children,” (June 3, 2020), available at: https://www.bbc.com/future/article/20200603-how-covid-19-is-changing-the-worlds-children

[5] Gunnar M. R. (2017). Social Buffering of Stress in Development: A Career Perspective. Perspectives on psychological science: a journal of the Association for Psychological Science, 12(3), 355–373. https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691616680612

[6] Children’s Bureau, Factsheet, Parenting a Child Who Has Experienced Trauma, (November 2014), available at: https://www.childwelfare.gov/pubPDFs/child-trauma.pdf; Administration for Children and Families, Information Memorandum, IM-20-02, Family time and visitation for children and youth in out-of-home care, (available at: https://www.acf.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/cb/im2002.pdf), pg 4.

[7] Id at 9.

[8] Id at 4.

[9] Smargia, Margaret. Visitation with Infants and Toddlers in Foster Care: What Judges and Attorneys Need to Know. American Bar Association and ZERO TO THREE, 2007, 5.

[10] American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Early Childhood, Adoption and Dependent Care. “Developmental Issues for Young Children in Foster Care.” Pediatrics 105(5), 2000, 1146.

[11] Edited by Charles H. Zeanah, Jr., MD. Handbook of Infant Mental Health, Third Edition. Guilford Press, 2009.

Hill, Sheri & Solchany, Joanne. “Mental Health Assessments for Infants and Toddlers,” American Bar Association Child Law Practice, Vol. 24, no.9, 2005, p. 139.

[12] Jones Harden, Brenda. Infants in the Child Welfare: A Developmental Framework for Policy and Practice, Zero To Three, 2007, p. 252.