Chapter Sections

Introduction1

Research compiled by the American Bar Association’s Opening Doors Project shows that lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and questioning (LGBTQ) youth2 in foster care are disadvantaged for many reasons, and judges and lawyers can help them. For example research statistics indicate that

- 70 percent of LGBTQ youth in group homes reported violence based on LGBTQ status.

- 100 percent of LGBTQ youth in group homes reported verbal harassment.

- 78 percent of youth were removed or ran away from placement because of hostility to LGBTQ status.

- Between 4 and 10 percent of youth in state care identified as LGBTQ.

- 30 percent of LGBTQ youth reported physical violence by their family after coming out.

- 80 percent of LGBTQ students reported verbal harassment at school (70 percent feel unsafe; 28 percent dropped out).

Research also demonstrates that LGBTQ youth are

- Punished for expressing LGBTQ status;

- Not allowed to participate in programming;

- Told “you are going to hell;” and

- Not allowed to dress or groom as they prefer.

The staff from the Opening Doors Project traveled to five cities (Denver, Colorado; Jacksonville, Florida; Nashville, Tennessee; New York City, New York; and Seattle, Washington) to conduct listening forums with LGBTQ youth who were in or recently out of foster care, and judges and lawyers from those cities. The following are things heard by the staff as they talked with participants at the listening forums:

- We met a transgender young woman who felt safer at school than in her “temporary” shelter that she had been in for months.

- We talked to a young man who had been in 37 homes and was told he was gay before he even knew what the word meant.

- We met young people who felt disrespected by the judges who heard their cases and youth who questioned why professionals in the child welfare system did not treat kids well.

- We also met a lesbian young woman whose lawyer was her best friend and the person she trusted the most.

Judges and lawyers expressed the following:

- “Ignorance can only be remedied with knowledge. The system is broken; the only way to change it is through advocacy.” 3

- “I have gender-neutral language when asking my clients about their dating life.”4

- “I have a folder on my bench with resources for different issues (e.g., domestic violence). If I had resources for LGBTQ youth, I would include them and give them to people that need it.”5

§1 The Role of the Court in Protecting LGBTQ

- Some studies suggest that LGBTQ youth are two times more likely to attempt suicide than their heterosexual peers.6

- Between 11 percent and 40 percent of homeless youth are LGBTQ.7 Over half of homeless youth have spent some time in foster care.8

- LGBTQ youth are two times as likely to be threatened or injured with a weapon at school and two times as likely to skip school because they feel unsafe.9 Sixty-nine percent of LGBTQ youth reported experiencing some form of harassment or violence.10

The reality is that the statistics and stories are mostly grim for LGBTQ youth in foster care. Whether they enter foster care because their parents reject them due to their LGBTQ status or they disclose their LGBTQ status while in foster care, these youth face discrimination, harassment, and violence because of their sexuality or gender identity.

Lawyers and judges can help change these statistics. Lawyers who develop relationships with LGBTQ clients and provide appropriate representation can make a difference for these youth. Judges who ask the right questions and insist on appropriate services and fair and respectful treatment can protect this vulnerable population and help them become successful adults. This chapter discusses the risks facing LGBTQ youth in foster care. It also describes the roles judges and lawyers must play in these young people’s lives to protect them from these risks and help them succeed.

§2 A Life of Risks

LGBTQ youth have special risks related to their sexual orientation and gender identity that set them apart from non-LGBTQ youth in foster care. The social stigma attached to LGBTQ people causes these youth to hide their identities, fear for their safety, and often turn to drugs to cope. Higher suicide rates and violence in schools are two of the many risk factors to be aware of when working with LGBTQ youth in foster care.

§2a Suicide

Studies show LGBTQ youth are twice as likely as non-LGBTQ youth to attempt suicide. Others put the number closer to four times as likely.11 Aside from typical adolescent turmoil, LGBTQ youth face significantly greater conflict due to their sexual orientation or gender identity. They do not have the same feelings as their peers about sexual attraction or sense of identity. During adolescence, youth explore their identities and find where they fit. LGBTQ youth struggle with loneliness and feeling different. As expressed by one youth, “I knew that I was different, no one ever told me, but I just knew.”12 This feeling, coupled with being in foster care and having limited support, makes some youth think they have no way out. One youth explains, “As I got older through high school, it started to get even worse because I attempted suicide many times. It was too much. It was like at first I did it because I wanted people to say hey look, you know, look at me, pay attention to me. But after that I was placed at St. Jude’s, and that’s when I started to realize and accept that I was gay.”13

§2b Homelessness

When youth disclose their LGBTQ status to their parents or foster parents, the result is sometimes devastating. They are often rejected by people they rely upon for housing, food, and unconditional love and acceptance. Some youth voluntarily leave to escape the harassment or violence they experience at home. Some youth are forced to leave because the family does not accept their LGBTQ status: “One day my father heard me [a male] talking on the telephone to a guy who I had met. When I got off the phone he just went crazy on me….He told me to get out and literally threw me out the front door. I was devastated and didn’t know where to go.”14 Some youth travel from sofa to shelter to street corner. They often have no permanent place to call home. On the streets they are more susceptible to violence and crime.

§2c School

Youth spend the majority of time at school. It is supposed to be a place to feel safe and accepted. Yet according to Karey Scheyd, Deputy Director of Parent Recruitment for the New York Administration for Children’s Services, “[s]afety holds different meaning for LGBTQ kids: School is hard. Any situation can mean danger. Just because they are in stable placement doesn’t mean they are safe. We are quick to assume that the world likes gay people. [The] simple fact of being queer puts people at risk (physically and mentally). Judges and lawyers should start with these understandings and then take the step to question safety.”

School is the place where youth learn to interact with peers and form trusting relationships that often last into adulthood. LGBTQ youth in foster care have the added burden of moving from placement to placement and changing schools. They experience harassment and rejection through multiple school placements. They often do not have supportive teachers or counselors to turn to for help. Many end up dropping out or doing poorly in their studies.

§2d Prejudicial Treatment

Seventy-four percent of LGBTQ youth in foster care believe they experience prejudicial treatment by service providers because of their sexual orientation or gender identity.15 Youth often believe professionals accept people regardless of their differences. Sometimes they are wrong. Many youth in foster care find the professionals who work with them are just as harmful as the parents who abused them or the peers who harassed them. This realization is harmful because youth feel they have nowhere to go for support. The people who are supposed to support, care, and provide treatment for them are often the perpetrators of the harassment, intolerance, and sometimes violence.

One LGBTQ youth reported that he was in a religious foster home where it was not okay for him to be gay: “I had my own lock box with my stuff in it. They broke into it one day while I was at school. When I got home, they had me all packed up, because I was gay. I left town.”16 Another youth reported, “When I was in a group home, I was assaulted because I’m gay. I didn’t appreciate that I had to take it. The staff knew what was going on but they didn’t do anything to stop it.”17

Still another youth reported that although most staff did not say anything to his face, he overheard staff saying things like “That new fag kid that just came in. [sic.] Why do they make us put up with these gay children? Why do they ship them here? No wonder their parents get rid of them.”18

§2e Substance Abuse

LGBTQ youth are twice as likely as heterosexual youth to abuse alcohol and eight times as likely to use cocaine/crack.19 Using and abusing illegal substances is a common way that youth escape their troubles. LGBTQ youth in foster care have especially high rates of substance abuse due to their circumstances. Isolation, rejection, harassment, and violence can all be forgotten by getting high. “[P]ot, acid, ecstasy, speed…I did it all. I just wanted to kill the loneliness I felt inside. I really didn’t care if I lived or died. Trying to deal with my identity was a really difficult time for me.”20 They have limited exposure to positive coping tools and turn to substances to deal with the problems in their life.

By becoming aware of the risks associated with LGBTQ youth in foster care, lawyers and judges can take steps to address these issues. The fact that a youth is LGBTQ should factor into placement, permanency, services, advocacy, and court rulings.

§3 Interacting With Youth

Judges and lawyers need to closely watch how they interact with LGBTQ youth. The following list is not exhaustive and should be supplemented based on your comfort level and knowledge of LGBTQ issues.

§3a Attitudes

Whether known or not, lawyers and judges have preconceived notions when representing a child client or presiding over a dependency case. Some are appropriate. For example

- Children shouldn’t live in unsafe homes.

- Youth are generally better off in family-like settings.

- Children need stability and permanency in their lives.

These notions are based on knowledge of the child welfare field, child development, and the best interests of children.

Some preconceived notions, however, can harm a youth and/or family. Some can be based on a lack of understanding and information. Judges must understand their own beliefs about sexual orientation and gender identity when presiding over dependency cases. They must also learn the issues facing LGBTQ youth in foster care. Remaining objective does not require a judge to be free of these beliefs; it requires a judge to recognize them and to make rulings without imposing them on children and families. For example, a judge may feel uncomfortable with gender nonconforming behavior but have to remain objective when determining how to keep a transgender girl safe in a group home.

§3b Confidentiality

Children’s lives in dependency cases are often publicized for many to examine. The social worker knows about the youth’s home life, school progress, doctor appointments, test results, friends and social activities, and frequency of therapy appointments. Foster parents get reports about youth before they come into their homes. These reports are filled with details about the youth and the birth family. One youth reported that his foster parents were given a report when he was placed in their home at age six stating that he was gay. He expressed dismay because at six years old he did not know what being “gay” meant.21 The lawyers know most things that the social worker knows and have read and discussed the results of health professionals’ reports. The judge hears it all. Although hearings may be closed, inevitably people who do not know the youth hear the most intimate details of the youth’s life.

Sexual orientation and gender identity are intimate issues. Heterosexual youth have trouble discussing these issues, but for LGBTQ youth, the situation is worse. Because stigma is often attached to LGBTQ people, youth may not disclose their status for fear of others finding out. Constantly living under this fear can spiral into any number of common risks facing LGBTQ youth. Lawyers and judges can help lift the fear and stigma by keeping communications confidential.

When representing a youth, the lawyer should explain that all communications between the youth and lawyer (except under a few circumstances) are confidential and that the youth should feel comfortable telling the lawyer anything. The lawyer must stick to that promise. Many times lawyers with good intentions disclose information to social workers, foster parents, the judge, and others because they think it is in the best interests of the child. If youth are promised confidentiality, they may be more likely to disclose their LGBTQ status. The lawyer and the youth can then work together to decide if and when the youth should tell others.

If a youth is represented by a GAL or CASA, there is no confidentiality requirement. The GAL or CASA must discuss confidentiality with the youth and explain what communications will and will not be shared.

§4 Defining Terms

§4a Lesbian

A lesbian is a female whose primary sexual and romantic attractions are to other females. Some lesbians have romantic attractions to males and some do not. It is important to note that some females who have sexual or romantic attractions with other females, sometimes exclusively, may not call themselves lesbians.

§4b Gay

A gay male is a male whose primary sexual and romantic attraction is to other males. He may have sexual and romantic attractions to males currently or has in the past. Some gay males may never have had sexual or romantic attractions to other males for a host of reasons (e.g., age, societal pressures, lack of opportunity, fear of discrimination) but nonetheless realize that their sexual and romantic attraction is mainly to other males. Some gay males have sexual and romantic attractions with females and some do not. Note that some males who have sexual and romantic attractions with other males, sometimes exclusively, may not call themselves gay.

“Gay” is also used as an inclusive term encompassing gay males, lesbians, bisexual people, and sometimes even transgender people. The term is still often used in the broader sense in spoken shorthand as in “The Gay Pride Parade is at the end of June.”

§4c Bisexual

Bisexual males and females have sexual and romantic attractions to both males and females. Depending upon the person, his or her attraction may be stronger to females or to males, or they may be equal. Some people who have sexual and romantic attractions to both males and females do not consider themselves bisexual. Bisexuals are also referred to as “bi.”

§4d Transgender

People who identify more strongly with the other gender than the one to which they were assigned (e.g., females who feel like males, or males who feel like females) are called “transgendered.” Some transgendered people may “cross-dress” or “do drag” regularly or for fun (and many of these people are comfortable in their assigned gender). Other transgendered people may take hormones of the opposite gender and/or have surgery in order to change their bodies to reflect how they feel inside. These people may also be called “transsexual.” Transgendered people may identify as heterosexual, homosexual, or bisexual.

§4e Genderqueer/Intergender

Genderqueer and intergender are catchall terms for gender identities other than man and woman. People who identify as genderqueer may think of themselves as being both male and female, as being neither male nor female, or as falling completely outside the gender binary. Some wish to have certain features of the opposite sex and not all characteristics; others want it all.

Some genderqueer people see their identity as one of many possible genders other than male or female, while others see “genderqueer” as an umbrella term that encompasses all of those possible genders. Some see “genderqueer” as a third gender to complement the traditional two, while others identify as genderless. Genderqueer people are united by their rejection of the notion that there are only two genders. The term “genderqueer” can also be used as an adjective to refer to any people who transgress gender, regardless of their self-defined gender identity.

§4f Questioning

Refers to a person for whom a fixed sexual orientation and/or gender identity is not clear. Some questioning individuals may ultimately “come out” as LGBT, whereas others may be seeking additional resources to help address their internal questions. It is not developmentally uncommon for adolescents to question their sexual orientation or gender identity.

§4g Queer

Some LGBT people, particularly young people, use the term “queer” to encompass the entire LGBT community. For these people, the term “queer” is positive and empowering. Other LGBT people find this term degrading.

§5 Additional Resources

National Organizations and Research

ABA Center on Children and the Law, Opening Doors Project; Opening Doors for LGBTQ Youth in Foster Care: A Guide for Lawyers and Judges: http://www.ct.gov/shp/lib/shp/pdf/aba-_opening_doors.pdf

It’s Your Life: Improving the Legal System’s Approach to LGBTQ Youth in Foster Care: http://www.americanbar.org/groups/child_law/projects_initiatives/itsyourlife.html

The Kids Are Listening (Social Media Project): http://www.thekidsarelistening.org/

Legal Services for Children/National Center for Lesbian Rights Model Standards Project, Model Standards Project LGBTQ Practice Guide: http://www.lsc-sf.org

National Center for Lesbian Rights:http://www.nclrights.org

Breaking the Silence: LGBTQ Foster Youth Tell Their Stories: DVD and Resource CD: http://www.nclrights.org/site/DocServer/NCLR_DVDorderform.pdf?docID=1701

LGBTQ Youth in Foster Care System Fact Sheet: http://www.nclrights.org/site/DocServer/LGBTQ_Youth_In_Foster_Care_System.pdf?docID=1341

Hidden Injustice: Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual and Transgender Youth in Juvenile Courts: http://www.lsc-sf.org/wp-content/uploads/hidden-injustice-low-res-final.pdf

Child Welfare League of America, Out of the Margins: A Report on Regional Listening Forums Highlighting the Experience of LGBTQ Youth in Care, http://www.cwla.org/programs/culture/glbtq.htm: The National Gay and Lesbian Task Force

Foster Care Laws and Regulations in U.S.: http://www.thetaskforce.org/reports_and_research/foster_care_regulations

ABA Child Law Practice, Representing Transgender Youth: Learning from Mae’s Journey: http://apps.americanbar.org/child/clp/archives/vol29/jan11.pdf

American Bar Association, Litigation Section, Children’s Rights Litigation, What Lawyers Need to Know About Representing LGBTQ Youth [Videos 1–4]:http://apps.americanbar.org/litigation/committees/childrights/video/1004-video-LGBT-video01.html

Sylvia Rivera Project, Know Your Rights: Transgender Youth in Foster Care: http://srlp.org/files/kyr%20foster%20care%20eng-.pdf

National CASA Association, The Connection

Addressing the Needs of LGBTQ Youth in Foster Care: http://nc.casaforchildren.org/files/public/site/publications/TheConnection/Fall2009/Cover_Story.pdf

American Bar Association, Children’s Rights Litigation Committee, Providing High-Quality Representation for LGBTQ Youth in Foster Care: http://apps.americanbar.org/litigation/committees/childrights/content/newsletters/childrens_winter2009.pdf

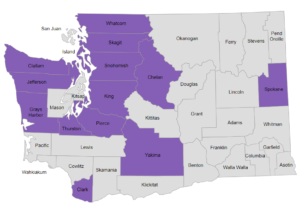

Local Organizations

A comprehensive list of local, state, and national LGBTQ organizations has been compiled by Safe Schools Coalition, an organization dedicated to helping schools become safe places for all children to learn, regardless of gender or sexual orientation. Safe Schools Coalition has a list of resources for every county in Washington State that can be found at: http://www.safeschoolscoalition.org/blackboard-washington.html.

Download this chapter: Chapter 11 – Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, and Questioning (LGBTQ) Youth in Foster Care

ENDNOTES

- Last updated Summer 2014. The information in this chapter consists of excerpts from Opening Doors for LGBTQ Youth in Foster Care: A Guide for Lawyers and Judges, published by the American Bar Association’s Center on Children and the Law. Mimi Laver & Andrea Khoury, Opening Doors for LGBTQ Youth in Foster Care: A Guide for Lawyers and Judges (2008), available at http://www.abanet.org/child/lgbtq.shtml. Special thanks go to Tricia S. Boerger of the Attorney General’s office, Cynthia Buhr of The Law Offices of Cynthia F. Buhr PLLC, and QLAW, the GLBT Bar Association of Washington, for their editorial assistance with this chapter.

- These terms and others are defined at the end of this chapter.

- Judge statement, Opening Doors Project listening forum, Jacksonville, FL, October 12, 2006.

- Lawyer statement, Opening Doors Project listening forum, Denver, CO, July 28, 2006.

- Lawyer statement, Opening Doors Project listening forum, Denver, CO, July 28, 2006.

- Stephen T. Russell & Kara Joyner, Adolescent Sexual Orientation and Suicide Risk: Evidence from a National Study, 91 Am. J. of Pub. Health 1276 (2001).

- Joseph J. Wardenski, A Minor Exception?: The Impact of Lawrence v. Texas on LGBT Youth, 95 Journal of Criminal Law and Criminology 1363 (2005).

- Gerald P. Mallon, We Don’t Exactly Get the Welcome Wagon: The Experience of Gay and Lesbian Adolescents in Child Welfare Systems (1998) [hereinafter Welcome Wagon].

- Massachusetts Dep’t of Educ., 2001 Massachusetts Youth Risk Behavior Survey Results (2002), available at http://www.doe.mass.edu/cnp/hprograms/yrbs/01/results.pdf.

- Joseph G. Kosciw, Ph.D., Gay, Lesbian and Straight Educ. Network (GLSEN), The 2003 National School Climate Survey: The School-Related Experiences of Our Nation’s Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual and Transgendered Youth (2004), available at http://www.glsen.org/binary-data/GLSEN_ATTACHMENTS/file/300-3.PDF.

- Patrick Healy, Suicides in State Top Homicides, Boston Globe, Feb. 28, 2001, at B1.

- Welcome Wagon at 22.

- Welcome Wagon at 28.

- Welcome Wagon at 50.

- Shannon Wilbur et al., CWLA Best Practices Guidelines: Serving LGBT Youth in Out-of–Home Care 6 (2006).

- Youth statement, Opening Doors Project listening forum, Jacksonville, FL, October 12, 2006.

- Child Welfare League of Am. & Lambda Legal Def. Educ. Fund, Out of the Margins: A Report on Regional Listening Forums Highlighting the Experiences of Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, and Questioning Youth in Care 22 (2006).

- Welcome Wagon at 62.

- Child Welfare League of Am. & Lambda Legal Def. Educ. Fund, Fostering Transitions: CWLA/Lambda Joint Initiative to Support Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, and Questioning (LGBTQ) Youth and Adults Involved with the Child Welfare System (2007), available at http://www.lambdalegals.org/take-action/tool-kits/getting-down-to-basics/risk-data.html.

- Welcome Wagon at 30.

- Youth statement, Opening Doors Project listening forum, Denver, CO, July 28, 2006.