Written in 2011 and updated in 2014 by Commissioner Michelle Ressa1

Chapter Sections

Introduction

When children are placed out-of-state, they are entitled to the same protections and services they would receive if they remained in Washington. The Interstate Compact on the Placement of Children (ICPC) provides a statutory means to ensure that children placed in another state have a suitable place to live and have access to the appropriate services for that child. Failure to follow the ICPC by Washington courts can lead to the harming of children—the antithesis of the dependency process.

If a child is subject to a dependency action, regardless of the stage of the proceeding, the ICPC applies.

§1 What is the ICPC?

- A uniform law that all 50 states have adopted verbatim.

- A contract between member jurisdictions.

- 10 Articles codified in RCW 26.34.010.

- 10 Administrative Regulations (These are not adopted as binding authority in Washington State, but they are persuasive interpretative authority).

- A law that benefits the sending states because

-

- The placement is supervised;

- The sending agency and court receive reports on the child’s adjustment and progress in placement; and

- The sending state does not lose jurisdiction over child.

- A law that benefits the receiving states because

-

- Prior approval of the placement ensures that the placement is appropriate; and

- It ensures that the receiving state’s laws have been followed.

§2 Types of Cases Not Subject to the ICPC (Regulation 3)

- Dissolution actions and establishment of parenting plans between parents.

- Custody cases involving relatives (to a specified degree) and parents.

-

- The specified degree includes stepparent, grandparent, brother, sister, uncle, and aunt.

- Tribal placements.

-

- The court must inquire whether the child is being placed on sovereign tribal land.

- The court must also inquire whether the receiving tribe has a contract with the receiving state for ICPC application. For example, some tribes contract with their state for child welfare services, home studies, and other similar services. If the receiving tribe has a contract with the receiving state, then the ICPC most likely applies to a placement with that tribe.

- If the tribe has a Title IV-E agreement with the receiving state, the ICPC will most likely apply.

- If the tribe assumes jurisdiction, there is no authority for a Washington court to act, so the ICPC does not apply.

- Out-of-State Visits (see also below).

- Placement of a child into another country.

- Placement of a child into a hospital or other medical facility, to any institution that cares for the mentally ill, or to a school.2

- Potentially, placement of child with a biological parent.3

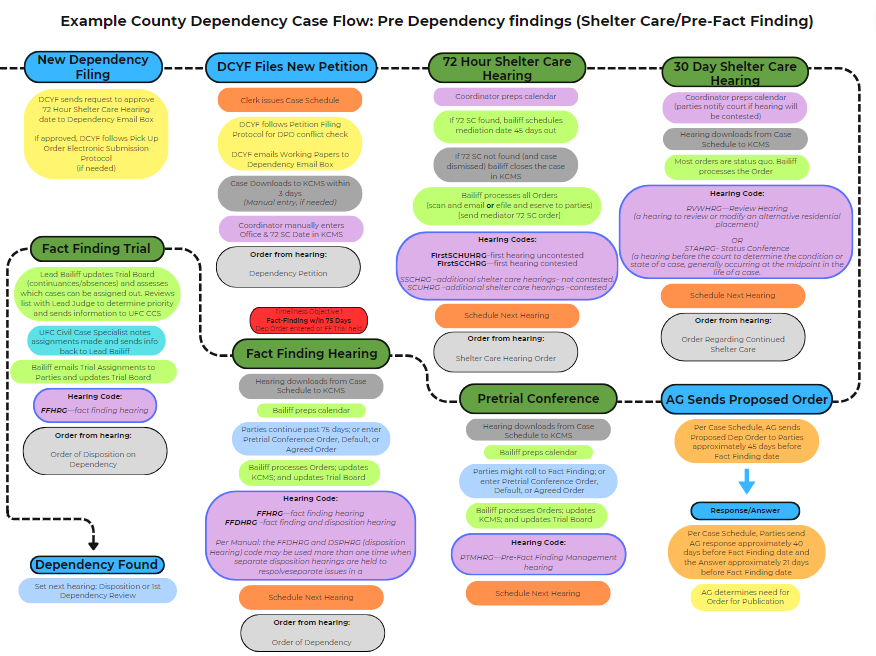

§3 Procedure

The process for placing a child in a receiving state involves several steps and several different personnel. It can be a lengthy process; however, a Washington court cannot place a child in the receiving state with a non-parent until or unless the receiving state approves. (See Violations section below.) Placement with a parent is more complicated. If the Washington Court is inclined to place a dependent child in another state without that state’s approval, the child and parent will not have access to services that can only be paid for by the Washington medical coupon. (See Placement with Parents below.)

The procedure for placement is as follows:

- The local Department of Children and Family Services (DCFS) office must request application of the ICPC through the Program Manager (also known as the Compact Administrator) in Olympia.

- There are several forms to fill out, and they must be completed correctly to avoid delay.

- The Program Manager in Olympia then contacts the receiving state to start the process.

- The receiving state addresses its questions and concerns through the Program Manager who then seeks answers from the local social worker.

- The receiving state then sends its approval or denial within 20 business days through the Program Manger in Olympia.

How to address delay

Not all social workers, AAGs, Public Defenders, and GALs will know or understand the ICPC process. The following measures can assist in addressing any delay that may arise:

- Specifically inquire at a court hearing about issues involving delay in the ICPC approval/denial. Ask the AAG or social worker to identify when the paperwork left Olympia and get answers about any delays.

- Require declaration or phone testimony from the ICPC Program Manger in Olympia.

- Set status reviews (weekly, bi-monthly, or monthly) to determine where the delay exists (whether with Washington or with the receiving state).

- Engage in direct communication with the receiving state ICPC Administrator during court hearings.

- Consider ordering specific action by the social worker, his or her supervisor, or the Washington ICPC Program Manager.

§4 Priority Placements [Regulation 7]

Timeframes for the compact administrators/program managers differ depending on whether or not the placement is a “priority” placement. Priority placements occur under the following circumstances:

- The proposed placement is with a parent, stepparent, grandparent, adult brother or sister, or adult uncle or aunt or guardian, and

- The child is under two years old; or

- The child is in an emergency placement; or

- The court finds the child has spent substantial time in the home of the proposed placement.

Even if these criteria are met, a child in the receiving state in violation of the ICPC does not qualify for priority processing. Your local AGO should have a form with the required findings that can be sent to the receiving state.

Placement with a parent

When the court wants to place a child with a parent, but does not want to dismiss dependency court jurisdiction over that child, a specific court order is needed showing that the case qualifies as a priority placement case.

The order must state that:

- The child is being placed with a parent; and

- The child is not already in the receiving state in violation of the ICPC; and

- one of the other factors above applies:

- The child is under two years old; or

- The child is in an emergency placement; or

- The court finds the child has spent substantial time in the home of the proposed placement.

Until recently, whether the ICPC applied to placement with a parent was not settled law in Washington. Many attorneys argued that the ICPC does not apply to placement with a parent. Their argument was essentially as follows: because ICPC article VIII does not mention parental placements and because the ICPC is to be construed liberally, the ICPC does apply to parental placements.4

A recent Division I decision affirmed this position, holding that the ICPC’s application to foster care placements did not extend to parental placements.5 The only federal court to have addressed the issue agrees, arguing that to construe placement of a child with his parent as a placement in foster care under the ICPC “would result in the anomalous situation of imposing a financial obligation upon a sending state that supersedes parents’ duty to support their children.”6 Similarly, a slight majority of courts that have addressed the issue have decided that the ICPC applies to a placement with a parent so long as the child remains subject to the jurisdiction of the juvenile court.7 Although this appellate decision is now precedential law for Division I, it is not necessarily the conclusion other divisions of the Washington State Court of Appeals will draw.8 Meanwhile, Washington will have to wait and see what this Division I decision does to the relationship our state has with the other 49 states under the ICPC. If we violate the ICPC laws of other states, our children may have more difficulty proceeding quickly to permanency.9

§5 Non-Priority Placements

Routine processing of other requests are not considered priority placements under Regulation 7. Placement requirements are not uniform among states. As a result, the court will need to know if the receiving state home study will meet Washington State standards (e.g., criminal background checks and child protective services agency checks) before approving the placement.

It is generally agreed among member states that a home study is to be completed within 30 working days from the date the worker receives the request. In reality, the completion date is closer to 60 actual days. Approval from the receiving state is good for six months. If no permanent placement is made within six months, the sending state must reapply. If the court is placing tribal children out-of-state, the child’s tribe has the authority to set that tribe’s community standards for home studies conducted within its jurisdiction.

§6 Visits [Regulation 9]

The question may arise as to whether a child is visiting another state or being placed in another state. A visit, even an “extended visit,” is not a placement subject to the ICPC. A visit is defined as having a beginning date and an ending date, and the court should expect the child to return to Washington. If a child is visiting another state, services are not likely available to them, and the state the child is visiting will not have approved a placement or made an evaluation of the appropriateness of the home. Further neither the child nor the home will be monitored.

If the child travels to another state pending an ICPC home study, a rebuttable presumption of placement arises. Consequently, the receiving state may deny the ICPC request because of a violation of the compact. (See other Consequences below).

§7 Consequences for Violations

First and foremost, the child may be harmed. In addition:

- The child will not have access to services because Washington DSHS cannot pay for out-of-state providers;

- The Washington social worker may be violating the other state’s law if it is determined that they are practicing social work in another state without a license by trying to conduct a “health and safety” check or home study in the other state;

- The court will have no authority to bring the child back to Washington;

- The next child placed in the receiving state will not receive timely services or evaluation of placement;

- Some states have adopted criminal offense provisions expressly for violation of the ICPC; and

- Judicial officers and attorneys must comply with the law. Case law describes attorneys sanctioned and suspended for failing to follow the ICPC, and the Canons of Judicial Conduct prohibit conduct that violates the law.

Caution: DSHS, attorneys, or GALs may ask the court to approve a placement that DSHS cannot approve because they have no ICPC approval. This is not appropriate. If Washington courts violate the ICPC and place children in another state without approval from the other state, we leave our children vulnerable and harm the ability of future children to have timely and appropriate placements in that state.

§8 Other Resources

- APHSA/National Council of Juvenile and Family Court Judges Manual, 2001

- Association of Administrators on the ICPC – http://aaicama.org/cms/

Download this chapter: Chapter 28 – Interstate Compact on the Placement of Children (ICPC)

ENDNOTES

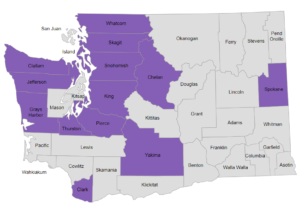

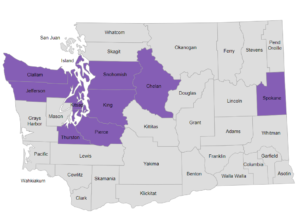

- Michelle Ressa was appointed to the Spokane County Superior Court bench in May 2007. Before that, she spent a year as the Superior Court Commissioner in Grant County. Michelle was born and raised in Spokane and graduated from the University of Washington in 1992 with a degree in Political Science. She graduated, cum laude, in 1996 from Gonzaga University School of Law. Michelle has spent her entire legal career working in the field of child welfare. Appointed in 1996 by then-Attorney General Christine Gregoire, Michelle represented the Department of Social and Health Services (DSHS) in dependency, termination, and licensing actions in Thurston, Lewis, and Mason Counties. Michelle also represented DSHS in King County for several years before taking a position representing Children’s Administration headquarters in 2002. Michelle also represented DSHS in civil tort cases for two years before her appointment to the bench. Michelle has conducted numerous hours of training for the courts, DSHS, the Attorney General’s office and the child welfare community. She has consistently showed her dedication and passion for children and families navigating their way through a complicated, emotional, and financially challenging legal system.

- See RCW 26.34.010, art. II, § d.

- See also §26.4; In re D.F.M., 157 Wn. App 179, 236 P.2d 961 (2010).

- See, e.g., In re D.F.M., 157 Wn. App. 179.

- See, e.g., In re D.F.M., 157 Wn. App. 179.

- McComb v. Wambaugh, 934 F.2d 474, 480 (3d Cir.1991).

- In re D.F.M. at 190.

- Although divisions of the Washington State Court of Appeals typically show deference to each other’s decisions, this horizontal stare decisis is aspirational and dependent on judicial self-restraint, unlike the inexorable command of vertical stare decisis. Kelly Kunsch, Stare Decisis: Everything You Never Realized You Need to Know, 52 Wash. State Bar News, Oct. 1998, at 31. As a result, Divisions II and III and lower courts within these divisions may adopt an alternative reading of the ICPC.

- See §26.7.