Marci Comeau[1]

2024[1]

“…The Due Process Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment protects the fundamental right of parents to make decisions concerning the care, custody, and control of their children.”[2] If the State seeks to interfere with this fundamental right, the legislature has provided a procedure by which a child may be declared “dependent[3].” The procedure includes a fact-finding trial or hearing in which the petitioner, generally the Department of Children, Youth and Families, (“the Department[4]”) bears the burden of establishing by a preponderance of the evidence that the child meets one of the statutory definitions of dependency.[5] If the court finds that the child is dependent, it then holds a hearing to determine placement of the child and the services to be provided to the family.[6]

Notice and Jurisdiction

Before a court can hear and adjudicate a dependency fact-finding trial, the Department must follow procedures set forth in chapter 13.34 RCW.[7] Those procedures include the filing of a petition and the issuance of a summons, attaching a copy of the petition, directing notice of the fact-finding hearing to the following parties:

- The child, if the child is 12 years old or older;[8]

- Parents;[9] guardians,[10] or custodians;[11]

- Other persons as appear to the court to be proper or necessary parties to the proceedings.[12]

Any petition filed by the Department must be verified, contain a statement constituting a dependency, and include the names, residence, and contact information (if known) of each parent, guardian, or custodian (“parent”)[13] of the child.[14]

The Department must properly serve the parties responding to the dependency petition in order for the court to have personal jurisdiction.[15] Pursuant to chapter 13.34 RCW, a party who can be found within the state must be personally served with the summons no later than fifteen court days before the fact-finding hearing.[16] If the party resides within the state and cannot be personally served, but the party’s address is known or can with reasonable diligence be ascertained, the Department can serve the summons on the party by mailing a copy by certified mail no later than fifteen court days before the fact-finding hearing, or by a time directed by the court.[17] If a party is outside of the state, but can be found, or their address is known or can with reasonable diligence be ascertained, the Department can serve the summons either by personal service or by certified mail at least ten court days before the fact-finding hearing, or by a time directed by the court.[18] If the party is not a resident of this state or the name, place of residence, or whereabouts of the party is unknown, and after due diligence, the Department has been unable to serve a party, the Department may seek an order directing the county clerk to publish notice to the party in the county in which the petition was filed.[19] If the party is believed to be a resident of another state or a county other than the county in which the petition was filed, notice must be published in the county in which the party is believed to reside.[20] The Department must also mail a copy of the notice, postage prepaid, to the party at their last known residence.[21]

Notice – Jurisdiction – ICWA

If the Department has reason to know that the child is or may be an Indian child, the Department must notify the parents or Indian custodian and the Indian child’s tribe or tribes.[22] Notice must occur by certified mail, return receipt requested, and by use of a mandatory Indian Child Welfare Act notice addressed to the tribal agent designated by the Indian child’s tribe or tribes for receipt of Indian Child Welfare Act notice, as published by the Bureau of Indian Affairs in the federal register.[23] If the identity or location of the parents or Indian custodian and the tribe cannot be determined, notice must be given to the secretary of the interior by registered mail, return receipt requested, in accordance with the regulations of the bureau of Indian affairs.[24] Copies of the notices, with return receipts or other proof of service must be filed with the court; copies of the Tribes’ responses should also be filed with the court.[25] The dependency fact-finding trial cannot be held until at least ten days after receipt of notice by the parent or Indian custodian and the tribe.[26] Further, the parent or Indian custodian, or the tribe, shall, upon request, be granted up to twenty additional days to prepare for the dependency fact-finding trial.[27] Failure to provide proper notice under the Indian Child Welfare Act is error.[28]

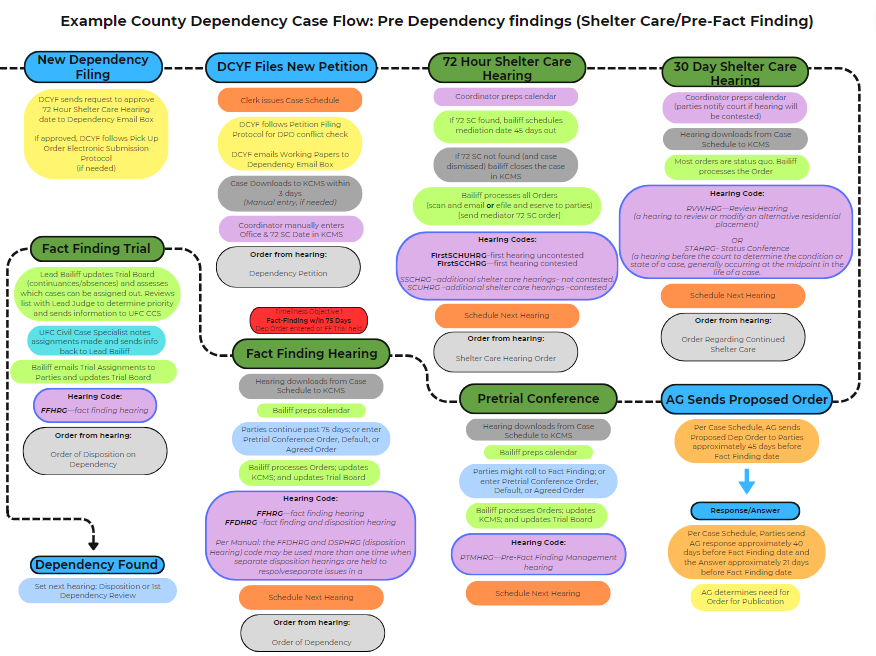

Timing

When Child Protective Services (CPS) determines that a report of abuse or neglect meets the legal definition of child abuse or neglect, the Department may assign the report for either investigation or family assessment.[29] When CPS assigns a report for investigation, it must complete its investigation[30] and issue a finding that the report of child abuse or neglect is founded[31] or unfounded.[32] A founded finding can be challenged through Department review.[33] If the report remains founded following agency review, an adjudicative administrative hearing, often referred to as a CAPTA[34] hearing, to contest the finding can be requested.[35] If the Department files a dependency petition based on the alleged abuse or neglect, the administrative hearing challenging the founded finding of abuse or neglect must be stayed (postponed) until the superior court has entered an order and findings regarding the dependency petition.[36]

The court shall hold a fact-finding hearing on a dependency petition no later than 75 daysafter the filing of the petition, unless the court finds exceptional reasons for a continuance.[37] The party requesting the continuance has the burden of proving by a preponderance of the evidence that exceptional circumstances exist.[38] The court shall give preference to those cases where the child is placed in out-of-home care.[39]

Pretrial Procedures

All hearings shall be public, except if the court finds that excluding the public is in the best interests of the child.[40] Whether courtroom proceedings should be closed to the public requires the court to make an individualized determination based upon five factors:

- The proponent of closure must make some showing of the need to do so, and the need involves a serious and imminent risk;

- Anyone present when the closure motion is made must be given an opportunity to object to the closure;

- The proposed method for curtailing open access must be the least restrictive means available to protect the threatened interest;

- The court must weigh the competing interest of the closure proponent and the public; and

- The order must be no broader in its application or duration than necessary to serve its purpose.[41]

Either parent, or the child’s attorney or the GAL, may move to close a hearing at any time.[42] The statute is silent as to whether the Department can seek to close a hearing.[43]

Any party may file a notice of disqualification[44] against a judge prior to that judge hearing the dependency fact-finding, so long as that judge has not exercised any acts of discretion in the dependency matter.[45]

Hearing

At the dependency fact-finding hearing, the Rules of Evidence apply.[46] The Department is required to prove that the child meets the definition of a dependent child by a preponderance of the evidence.[47]

The Department must establish that the child meets one of the statutory definitions of a “dependent child” under RCW 13.34.030(6). A dependent child is one who:

- has been abandoned;[48]

- is abused or neglected, as defined in chapter 26.44 RCW, by a person legally responsible for the care of the child;[49]

- has no parent, guardian, or custodian capable of adequately caring for the child, such that the child is in circumstances which constitute a danger of substantial damage to the child’s psychological or physical development[50];

- is receiving extended foster care services[51]; or

- is a victim of sex trafficking or severe forms of trafficking in persons under the trafficking victims protection act of 2000, 22 U.S.C. Sec. 7101 et. seq., when the parent is involved in the trafficking, facilitating the trafficking, or should have known that the child is being trafficked.[52]

In determining whether the Department has proven that a child is dependent as defined under the statute, the Department is not required to prove it has made reasonable efforts to prevent removal.[53]

Judicial officers may take notice of undisputed facts and may apply common sense based on their experience, but they cannot consider evidence outside the record.[54] Judicial officers cannot take judicial notice of testimony from a prior dependency proceeding.[55] Experts may testify about information, including out of court statements, that they considered in reaching their opinions; however, the court cannot consider this information as substantive evidence unless it is otherwise admissible.[56] The court may not consider or review the Department’s social file or social study prior to, or in connection with, the fact-finding hearing, except as otherwise admissible under the rules of evidence.[57]

If the Department does not meet its burden of proof in showing that the child is dependent, the petition is dismissed and the child is returned to the custody of the parent.[58] If the Department does not meet its burden of proof, failure to dismiss the petition at the conclusion of the trial is error.[59]

Findings of Fact and Conclusions of Law

If the Department does meet its burden of proof, the court must enter written findings of fact, stating the reasons for finding the child is dependent, and conclusions of law.[60] The written findings should include, and evaluate the facts in the context of, the statutory language, and should not merely incorporate the court’s oral ruling.[61] The findings of fact should identify the specific evidence upon which the court relied to support its ultimate findings.[62]

If the court enters a dependency order against a parent, the parent may appeal that order as of right.[63]

Default Orders of Dependency

If the parent does not appear at the dependency fact-finding hearing after receiving proper notice, the Department may request to enter an order of dependency against the parent by default.[64] If the parent has previously appeared in the dependency proceeding, either personally or through counsel, the parent is entitled to notice of the Department’s intent to proceed by default at the fact-finding hearing; however, if the parent has never appeared in the proceeding, no notice is required.[65]

Agreed Orders or Settlements

The parent of a child may waive their right to a fact-finding hearing by stipulating, or agreeing, to the entry of an order establishing that the child is dependent.[66] The agreed order must be signed by the parent and their attorney, unless the parent has waived their right to an attorney in open court.[67] The agreement must also be signed by the Department and by the child’s attorney, guardian ad litem, or court-appointed special advocate.[68] If the Department is not the petitioner and is required by the order to supervise the placement or to provide services to any party, it must also agree to and sign the order[69]. The agreed order of dependency is subject to approval of the court.[70] The court must receive and review the Department’s social study before entering a stipulated or agreed order and must consider whether the order is consistent with the allegations of the dependency petition and the problems that necessitated the child’s placement in out-of-home care.[71]

To approve an agreed order, the parent and their attorney must appear before the court, and the court, within available resources, must inquire and establish on the record that:

- The parent understands the terms of the order they have signed, including their responsibility to participate in remedial services as provided in any disposition order;

- The parent understands that entry of the order starts a process that could result in the filing of a petition to terminate their relationship with the child within the time frames required by state and federal law if they fail to comply with the terms of the dependency or disposition orders or fail to substantially remedy the problems that necessitated the child’s placement in out-of-home care;

- The parent understands that the entry of the stipulated or agreed order of dependency is an admission that the child is dependent and has the same legal effect as a finding by the court that the child is dependent by at least a preponderance of the evidence, and that the parent shall not have the right in any subsequent proceeding for termination of parental rights or guardianship to challenge or dispute the fact that the child was found to be dependent; and

- The parent knowingly and willingly stipulated and agreed to and signed the order or orders, without duress, and without misrepresentation or fraud by any other party.[72]

If a parent stipulates, or agrees, to entry of an order of dependency, but then fails to appear before the court, the court may enter the order of dependency if the court finds the parent had actual notice of the right to appear but chose not to do so.[73]

A parent may choose to waive their presence in court for entry of the stipulated, or agreed, order of dependency by submitting to the court, through counsel, a stipulated or agreed dependency fact-finding statement.[74]

ENDNOTES

[1] Originally written by Judge Kitty-Ann van Doorninck; 2014 Updates by Commissioner Michelle Ressa

[1] Marci Comeau (she/her) is a Managing Attorney for the Washington State Office of Public Defense (OPD) Parents Representation Program. Prior to joining OPD, Marci served as an Administrative Law Judge for the Washington State Office of Administrative Hearings, both in the Social and Health Services and Employment Security Divisions. From 2012 to 2020, Marci worked for the King County Department of Public Defense for 8 years, representing parents and children in dependency proceedings. From 2006 to 2012, Marci worked as an Assistant Attorney General, representing DSHS in dependency proceedings. Throughout her career, Marci has enjoyed providing local, statewide, and national trainings to stakeholders in the juvenile dependency system on various topics, including dependency practice and procedure, discovery, the harm of removal, the mental health of dependency practitioners, and anti-racist dependency practice. Marci received her undergraduate degree, magna cum laude, from the University of Washington in 2001, and her Juris Doctorate, summa cum laude, from Seattle University in 2006.

[2] Troxel v. Granville, 530 U.S. 57 (2000); see also Santosky v. Kramer, 455 U.S. 745 (1982); Stanley v. Illinois, 405 U.S. 645 (1972); Wisconsin v. Yoder 406 U.S. 205 (1972); Prince v. Massachusetts, 321 U.S. 158 (1944); Pierce v. Society of Sisters, 268 U.S. 510 (1925); Meyer v. Nebraska, 262 U.S. 390 (1923).

[3] RCW 13.34.030(6).

[4] Generally, the Department of Children, Youth, and Families (DCYF) is the petitioner in a dependency action, but “any person” may file a dependency petition. RCW 13.34.040(1); see also In re Dependency of E.H., 191 Wn.2d 872 (2010) (“[T]he State is not always a party, let alone represented by counsel. Dependency petitions may be brought by “[a]ny person.” RCW 13.34.040(1). Family members can petition a court to find a child dependent in order to be granted guardianship over the child. Juveniles themselves may initiate dependency actions in order to gain a predicate order to obtain special juvenile immigrant status and the resulting relief from removability. 8 U.S.C. § 1101(a)(27)(J).”) Because privately-filed cases represent a small fraction of dependency actions brought in Washington State, and for consistency and clarity, this chapter will refer to the petitioner as “the Department.”

[5] RCW 13.34.110(1).

[6] RCW 13.34.110(4).

[7] See, e.g., Olson v. Olson, 46 Wn.2d 246 (1955).

[8] RCW 13.34.070(1).

[9] RCW 13.34.030(19) (meaning “the biological or adoptive parents of a child, or an individual who has established a parent-child relationship under RCW 26.26A.100, unless the legal rights of that person have been terminated by a judicial proceeding pursuant to this chapter, chapter 26.33 RCW, or the equivalent laws of another state or a federally recognized Indian tribe”); see also RCW 13.34.070(1).

[10] RCW 13.34.030(11) (meaning “the person or agency that: (a) Has been appointed as the guardian of a child in a legal proceeding, including a guardian appointed pursuant to chapter 13.36 RCW; and (b) has the legal right to custody of the child pursuant to such appointment. The term “guardian” does not include a “dependency guardian” appointed pursuant to a proceeding under this chapter.”)

[11] RCW 13.34.070(1).

[12] RCW 13.34.070(1) (including Court-Appointed Special Advocates (CASAs), Guardian ad Litems (GALs), tribes, and attorneys for parties).

[13] Parents, guardians, and legal custodians may all be respondents to a dependency petition. For purposes of brevity, clarity, and consistency, this chapter will refer to these respondents as “parent” or “parents.”

[14] RCW 13.34.040(5).

[15] Painter v. Olney, 37 Wn. App. 424 (1984).

[16] RCW 13.34.070(8); see also Matter of Dependency of G.M.W., 24 Wn. App. 2d 96 (2022) (service pursuant to RCW 4.28.080(16) satisfies dependency statute.)

[17] RCW 13.34.070(8).

[18] RCW 13.34.070(8).

[19] RCW 13.34.080(1).

[20] RCW 13.34.080(1)(b).

[21] RCW 13.34.080(1).

[22] RCW 13.34.070(10); RCW 13.38.070; see also Matter of Dependency of Z.J.G., 471 P.3d 853 (2020) (describing importance of broad interpretation of “reason to know” in order to trigger formal notification to tribes for child custody proceedings; “Lack of notice repeats the historical harms that predicated the passage of ICWA and WICWA: Indian children are more likely to be taken and then lost in the system, often adopted when legally free, primarily to non-Native homes; tribes are denied the opportunity to make membership determinations; and tribes are unable to intervene in the case or exercise jurisdiction.”)

[23] RCW 13.38.070(1).

[24] RCW 13.38.070(1).

[25] 25 C.F.R. § 23.111(a)(2); see also In re Dependency of E.S., 92 Wn. App. 762 (1998) (The court strongly encourages the State to file evidence of its compliance with ICWA notice requirements because “the burden of proving notice is on the State” and “filing of proof of service in the trial court’s file would be the most efficient way of meeting that burden of proof.”).

[26] RCW 13.38.070(1).

[27] RCW 13.34.070(1).

[28] In re Dependency of T.L.G., 126 Wn.App. 181 (2005) (violation of notice requirements of Indian Child Welfare Act warranted remand to trial court).

[29] RCW 13.34.030(12)(a).

[30] RCW 26.44.030(13)(a).

[31] WAC 110-30-0020 (meaning “the determination following an investigation by CPS that based on available information it is more likely than not that child abuse or neglect did occur.”)

[32] WAC 110-30-0020 (meaning “the determination following an investigation by CPS that based on available information it is more likely than not that child abuse or neglect did not occur or there is insufficient evidence for the department to determine whether the alleged child abuse did or did not occur.”)

[33] RCW 26.44.125.

[34] Child Abuse Prevention and Treatment Act, P.L. 117-348.

[35] RCW 26.44.125(5).

[36] WAC 110-30-0300(1).

[37] RCW 13.34.070(1); but see also JuCR 3.4(c) (allowing continuance for “good cause.”)

[38] RCW 13.34.070(1), WAC 110-30-0300(1).

[39] JuCR 3.4(c).

[40] RCW 13.34.115(1).

[41] Seattle Times Co. v. Ishikawa, 97 Wn.2d 30 (1982).

[42] RCW 13.34.115(2).

[43] RCW 13.34.115(2).

[44] RCW 4.12.050.

[45] In re Dependency of Hiebert, 28 Wn. App. 905 (1981); In re Gibson, 4 Wn. App. 372 (1971); see also McDaniel v. McDaniel, 64 Wn.2d 273 (1964); see also Hiebert, 28. Wn. App. 905 (1981) (routine appointments and setting the case for trial do not involve discretion, for purposes of whether a party may file an affidavit of prejudice).

[46] RCW 13.34.110(1); JuCR 3.7(b).

[47] RCW 13.34.110(1); JuCR 3.7(c); In re Schermer, 161 Wn.2d 927 (2007); In re Chubb, 46 Wn. App. 530 (1987).

[48] A child is “abandoned” when the child’s parent, guardian, or other custodian has expressed, either by statement or conduct, an intent to forego, for an extended period, parental rights or responsibilities despite an ability to exercise such rights and responsibilities. If the court finds that the petitioner has exercised due diligence in attempting to locate the parent, no contact between the child and the child’s parent, guardian, or other custodian for a period of three months creates a rebuttable presumption of abandonment, even if there is no expressed intent to abandon. RCW 13.34.030(1).

[49] “‘Physical abuse’ means the non-accidental infliction of physical injury or physical mistreatment on a child.” Physical abuse includes, but is not limited to, actions such as throwing, kicking, burning, or cutting a child; striking a child with a closed fist; shaking a child under age three; interfering with a child’s breathing; threatening a child with a deadly weapon; or doing any other act that is likely to cause and which does cause bodily harm greater than transient pain or minor temporary marks or which is injurious to the child’s health, welfare, and safety. WAC 110-30-0030(1).

“Sexual abuse” means committing or allowing to be committed any sexual offense against a child as defined in the criminal code. The intentional touching, either directly or through the clothing, of the sexual or other intimate parts of a child or allowing, permitting, compelling, encouraging, aiding, or otherwise causing a child to engage in touching the sexual or other intimate parts of another for the purpose of gratifying the sexual desire of the person touching the child, the child, or a third party. A parent or guardian of a child, a person authorized by the parent or guardian to provide childcare for the child, or a person providing medically recognized services for the child, may touch a child in the sexual or other intimate parts for the purposes of providing hygiene, child care, and medical treatment or diagnosis. WAC 110-30-0030(3).

““Negligent treatment or maltreatment” means an act or a failure to act, or the cumulative effects of a pattern of conduct, behavior, or inaction, that evidences a serious disregard of consequences of such magnitude as to constitute a clear and present danger to a child’s health, welfare, or safety. WAC 110-30-0030(5).

[50] See Matter of Z.A., 540 P.3d 173 (2023) (parent’s failure to protect from other parent’s drug use supported conclusion that children had no parent capable); In re Dependency of Schermer, 161 Wn.2d 927 (2007) (dependency based upon no capable parent allows consideration of child’s special needs and any limitations in parent’s ability to respond to those needs); In re Dependency of Brown, 149 Wn.2d 836 (2003); (father failed to demonstrate present capacity to provide stable home posing no danger of substantial damage to child’s physical or psychological development); but see also In re Welfare of Ca.R., 191 Wn. App. 601 (2015) (child is not dependent if a capable parent exists); In re Walker, 43 Wn.2d 710 (1953) (existing ability or capacity of parents to adequately and properly care for children is inconsistent with dependency).

[51] Extended foster care services are available to youth who are eighteen years and older and who have been previously adjudicated dependent. RCW 13.34.267.

[52] 2SSB 6006, Sec. 4 (2023).

[53] Matter of Welfare of C.W.M., 533 P.3d 1199 (2023) (“[d]uring the factfinding hearing, the court may consider the past involvement of child protective services for the purpose of establishing the Department’s reasonable efforts, but only as to disposition and placement.” (Emphasis added.))

[54] Matter of Dependency of R.L.L., 540 P.3d 135 (2023).

[55] Matter of Dependency of R.L.L., 540 P.3d 135 (2023).

[56] Matter of Dependency of R.L.L., 540 P.3d 135 (2023); In re Welfare of X.T., 174 Wn. App. 733 (2013).

[57] RCW 13.34.110(3)(a).

[58] Lee v. State of Washington, Dept. of Social and Health Services, 189 Wn. App. 381 (2015).

[59] Lee v. State of Washington, Dept. of Social and Health Services, 189 Wn. App. 381 (2015) (trial court erred when it failed to dismiss dependency petition after concluding Department had not met its burden of proof, but instead repeatedly continued petition and supervision of family).

[60] RCW 13.34.110(1); CR 52.

[61] See Matter of Dependency of Q.S., 22 Wn. App. 2d 586 (2022).

[62] See Matter of Dependency of Q.S., 22 Wn. App. 2d 586 (2022).

[63] In re Dependency of Brown, 149 Wn.2d 836 (2003).

[64] See CR 55(a).

[65] CR 55(a)(3).

[66] RCW 13.34.110(3)(a).

[67] RCW 13.34.110(3)(a).

[68] RCW 13.34.110(3)(a).

[69] RCW 13.34.110(3)(a).

[70] RCW 13.34.110(3)(b).

[71] RCW 13.34.110(3)(b).

[72] RCW 13.34.110(3)(c).

[73] RCW 13.34.110(3)(c).

[74] RCW 13.34.110(3)(c).