Carissa Greenberg[1]

2022[i]

Introduction

The federal government’s entry into the child welfare field is relatively recent. It has only been during the past approximately 50 years that Congress has addressed child welfare issues (although it provided assistance to children living in poverty before then). Since the mid-1970s, through a number of federal funding statutes, Congress has shaped the public policy of the child welfare system and has established the parameters of juvenile dependency and termination of parental rights law in all 50 states. As a result, the delivery of child welfare services—which includes child protective services, family support services, foster care, kinship care, dependency and termination of parental rights proceedings, guardianships, adoptions and adoption support—involves a complex interweaving of federal and state laws. This section is intended to provide a brief overview of the relevant federal laws.

Federal statutes affecting the child welfare system fall into two basic categories: (1) funding statutes (those statutes that condition child welfare funding on the state’s compliance with federal mandates) and (2) substantive or mandatory law.

Funding Legislation

The federal government supports states’ various child welfare services, administrative support, foster care maintenance, medical services, and adoption support services. In order to receive federal funds, the state, including the state agency that administers child welfare services, service providers, and the courts, must follow federal law and guidelines. The following statutes are the primary sources of federal funds for child welfare cases.

Title IV of the Social Security Act, particularly Parts IV-B and IV-E, establishes the conditions for states participating in the federal funding of child welfare programs. When Congress passes a new bill affecting child welfare, the bill generally amends Title IV of the Social Security Act. The following acts amend different sections of Parts IV-B and IV-E. These acts, such as the Adam Walsh Act and the Adoption and Safe Families Act of 1997 (ASFA), often are referred to separately. However, they are contained within Title IV-B or IV-E.

Adoption Assistance and Child Welfare Act of 1980: This law (P.L. 96-272) requires that states that receive federal foster care and adoption support funds must provide “reasonable efforts” to keep families together and to reunite them when children are placed out of home. It requires the state to have an approved plan for providing foster children with individual case planning, permanency planning, and, when appropriate, placement with relatives. It also establishes the federal adoption support program.

Adoption and Safe Families Act of 1997 (ASFA): ASFA (P.L. 105-89) amended the Adoption Assistance and Child Welfare Act (Title IV-E). It changed the primary focus of child welfare programs from family preservation and reunification to safety of the child and, in order to provide stability and permanency for children, limited the time for parents to correct the deficiencies that resulted in out-of-home placement.

The ASFA amendments:

- Require that a child’s safety must be the paramount consideration when family preservation or family reunification is the goal;

- Provide certain exceptions to the reasonable efforts requirements of the Adoption Assistance and Child Welfare Act, short timelines, and less stringent conditions for seeking termination of parental rights;

- Require a 12-month time frame for permanency hearings and a definitive permanent plan for the child;

- Require background checks for all prospective foster and adoptive parents; and

- Require reasonable efforts be made to place children in a timely manner when adoption is the permanent plan.

Title IV-E has specific requirements impacting juvenile courts. These requirements relate to findings that must be made in the first order authorizing the removal of the child from the parent’s care and the state’s compliance with the reasonable efforts mandate. The chart following this chapter illustrates the impact of failure to meet Title IV-E mandates.

Family Preservation and Family Support Program (Promoting Safe and Stable Families): First passed in 1993 (P.L. 103-66) and then reauthorized in 1997 as part of the Adoption and Safe Families Act of 1997, this law provides funding for family preservation and community-based family support services.

Adam Walsh Child Protection and Safety Act: Passed in 2006 and effective in Washington in July 2007 (P.L. 109-248), this law amends Title IV-E to require additional criminal and child abuse/neglect background checks of prospective foster, relative, and adoptive parents, as well as of adults living in the homes of those persons.

Safe and Timely Interstate Placement of Foster Children Act of 2006: This Act (P.L. 109-239) amends Titles IV-B and IV-E and sets a 60-day time frame for completing interstate home studies; gives foster caregivers a right to notice and an opportunity to be heard in juvenile court proceedings regarding a child in their care; and requires medical and education records be provided to foster caregivers and to youths who exit foster care at age 18.

Preventing Sex Trafficking and Strengthening Families Act: Passed in 2014, this Act (P.L. 113-183) amends Titles IV-E and IV-B. Taken together, these amendments:

- Address sex trafficking by requiring Title IV-E agencies to identify, document, and determine appropriate services for children in their placement, care or supervision who are or who are at-risk of becoming a sex trafficking victim; report to law enforcement within 24 hours children3who the agency identifies as being a sex trafficking victim; and develop a protocol to determine, following a child’s unauthorized absence from foster care, whether the child is a sex trafficking victim.

- Ensure foster parents have skills and knowledge about the “reasonable and prudent parent standard.”

- Limit another planned permanent living arrangement as a permanency plan to only youth who are age 16 and older and add case plan and case review requirements for such youth.4

- Add case plan and case review requirements for youth age 14 or older.

- Require public child welfare agencies to provide youth aging out of foster care (unless they have been in foster care for less than six months) with his/her birth certificate, Social Security card, driver’s license or identification card, health insurance information, and medical records.

- Modify the Family Connection grant and the Chafee program grant.

- Reauthorize Adoption and Legal Guardianship Incentive Payments and create new incentive categories.

Family First Prevention Services Act (FFPSA): Enacted in 2018, and effective in Washington in 2019 (Laws of 2019, ch. 172), FFPSA (P.L. 115-123) amended Title IV-E to:

- Allow states to use federal funding for certain preventative services for families with children at risk of entering foster care and pregnant or parenting youth in foster care;

- Limit the group care placements that are eligible for federal funding to those facilities that care for more than six children and meet the definition of qualified residential treatment programs; and

- Require the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Administration for Children and Families to issue model foster care licensing standards.[ii]

Child Abuse Prevention and Treatment Act (CAPTA): First passed in 1974 to provide funding to assist states in developing Child Protective Services (CPS) systems, CAPTA was amended in 1996 (PL. 104-235) to require states to develop and implement procedures for reporting suspected child abuse and neglect, for investigating such reports, and for taking steps to protect children found to be at risk of harm.

CAPTA was again amended in 2015 by the Justice for Victims of Trafficking Act (P.L. 114-22), which expands the definition of “child abuse and neglect” and “sexual abuse” to include victims of sex trafficking. It also requires that states have provisions and procedures to identify and assess all reports involving children known or suspected to be victims of sex trafficking, and to train child protective services workers to serve such victims.

Multiethnic Placement Act (MEPA) and Interethnic Placement Act (IEPA): Together these two laws prohibit agencies that receive federal funding under Titles IV-B and IV-E of the Social Security Act from delaying or denying a child’s foster or adoptive placement on the basis of a child’s or the prospective foster or adoptive parent’s race, color, or national origin.

Foster Care Independence Act of 1999 (Chafee Act): This law requires states to provide transition services to youths, ages 18 to 21, who were formerly in foster care. The services are intended to aid the youths in achieving independence and may include education, employment-related training or services, personal and emotional support services, and financial assistance and housing.

Social Security Act Title XIX (Medicaid): All children in foster care and on adoption support are eligible for medical financial assistance through Medicaid. The program pays for necessary medical care to providers who agree to participate in the program.

Personal Responsibility and Work Opportunity Reconciliation Act (PRWORA, also known as the Welfare Reform Act): Although not a child welfare law, this act amends the Social Security Act and impacts children in the child welfare system by significantly limiting the federal funds available to non-documented aliens and by limiting the Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) grants available to parents and relatives.

Substantive Legislation

In addition to laws conditioning funding on compliance with certain standards or requirements, the U.S. Congress has passed substantive laws that impact the child welfare system. The most important are the following.

Indian Child Welfare Act (ICWA)

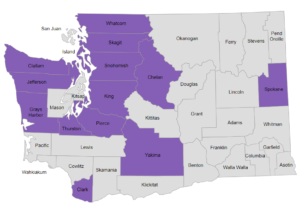

Enacted in 1978 (P.L. 95-608) this law recognizes the importance of maintaining a child’s connections with his or her Indian tribe and its cultural heritage when an Indian child is involved in the provision of foster care and adoption services. The law sets standards for the removal of Indian children, as defined in the act, from their families and sets standards establishing priorities for placement of Indian children in foster or adoptive homes. It also requires notice of juvenile dependency and termination proceedings to the tribe of an Indian child. Washington implemented the Washington State Indian Child Welfare Act (WSICWA) in 2011, which works in tandem with ICWA.

In June 2016, the Department of the Interior Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA) published regulations (25 C.F.R. Part 23) that are effective for proceedings initiated on or after December 12, 2016. The regulations provide clarity about ICWA requirements and address both voluntary and involuntary child custody proceedings. Of particular note, the regulations provide a definition of “active efforts” and include 11 non-exclusive examples. Additionally, the regulations require that at the commencement of each proceeding, state courts ask each participant whether the participant “knows or has reason to know” the child is an Indian child. The regulations further clarify when there is “reason to know” the child is an Indian child (25 C.F.R. 23.107(c)). If there is “reason to know” the child is an Indian child, then the court treats the child as an Indian child unless and until it is determined on the record that the child is not Indian. The regulations address when ICWA’s placement preferences apply, what the placement preferences are, how the court can make a determination of “good cause” to depart from those placement preferences, the burden of proof for doing so, and what evidence cannot be considered when making such a determination.

Fostering Connections to Success and Increasing Adoptions Act

Enacted in 2008, this law increased incentives for and the ability for relatives to care for children in foster care, and it extended federal support for youth to age 21. Since 2011, Washington has adopted legislation implementing the federal law by permitting foster youth to stay in foster care to continue their education efforts provided that the youth is enrolled and participating in a secondary education program or working toward a GED, a post-secondary or vocational educational program, a program or activity designed to promote or remove barriers to employment, or who are either employed for 80 or more hours per month or incapable of engaging in any of the aforementioned activities because of a medical condition that is supported by regularly updated information.

Immigration Laws (Special Immigrant Juvenile Status)

Part of the immigration statute, this law provides an avenue for undocumented children who are dependent because of abuse, neglect, or abandonment and who are likely to remain in long-term care to obtain a permanent residency permit to remain in the United States. The status must be sought (and granted) while the child is “dependent.” Although the status is obtained through immigration proceedings, it requires that a juvenile court enter an order finding the child dependent; that reunification with a parent is not viable because the child was abused, neglected or abandoned;, and that return to the care of the parent in the country of origin is not in the child’s best interests.

Conventions and Treaties

The United States is also a signatory to a number of agreements with other nations. These agreement, treaties, or conventions address numerous legal issues that range from service of process to provision of services and approval of caretakers that may arise when children who are citizens of other countries are involved in legal proceedings in the United States and when U.S. children are being placed for adoption or foster care in other countries.

APPENDIX 1: Title IV-E Findings

|

FEDERAL REQUIREMENTS Title IV-E of the Social Security Act, 42 U.S.C. § 670, et seq. |

RESULT IF NO FINDINGS ARE ENTERED |

||

|

First Order Authorizing Removal of the Child From the Home |

|

||

|

Court must make a finding that continuance in the home of the parent or legal guardian would be contrary to the child’s welfare and/or that it is in the child’s best interest to be placed in substitute/out-of-home care. 42 U.S.C. § 672(a)(1)(A), (a)(2)(A)(ii); 45 C.F.R. § 1356.21(c).

This finding must be made at the time of the first court ruling authorizing removal of the child from the home. 45 C.F.R. § 1356.21(c). This includes cases that begin as Child in Need of Services (CHINS) proceedings and cases in which a child is first removed as an offender and placed in detention. |

The state is never eligible for Title IV-E funding. This includes both foster care and adoption assistance. 45 C.F.R. § 1356.21(c). |

||

|

Court must order that the placement and care authority are the responsibility of the state agency or any other public agency with whom the responsible state agency has an agreement. 42 U.S.C. § 672(a)(1)(A), (a)(2)(B); 45 C.F.R. § 1356.71(d)(1)(iii). |

The state receives no funding until the findings are made.

|

||

|

Court must make a finding that reasonable efforts have been made to prevent or eliminate the need for removal. 42 U.S.C. § 672(a)(1)(A), (a)(2)(A)(ii); 45 C.F.R. § 1356.21(b)(1). See also 42 U.S.C. § 671(a)(15).

This finding must be made within 60 days of the date of removal. 45 C.F.R. § 1356.21(b)(1)(i). |

The state is never eligible for Title IV-E funding and this includes both foster care and adoption assistance. 45 C.F.R. § 1356.21(b)(1)(ii). |

||

|

Case Review/Status Review Hearings |

||

|

Court must review the child’s status and safety no less frequently than once every six months from the date the child entered foster care, in order to make the required findings. 42 U.S.C. § 675(5)(B); 45 C.F.R. § 1355.34(c)(2)(ii). See also 42 U.S.C. § 671(a)(16); see also 42 U.S.C. § 675(5)(F) (definition of the date the child entered foster care), 45 C.F.R. § 1355.20 (definition of the date the child entered foster care).

|

Failure to make these findings and/or failure to timely hold the review causes financial consequences due to noncompliance with the state plan. |

|

|

Permanent Plan Hearings |

||

|

Court must hold a permanency hearing to select a permanent plan no later than 12 months from the date the child entered foster care, and must hold subsequent permanency plan hearings every 12 months thereafter. 45 C.F.R. §§ 1355.20, 1356.21(b)(2)(i); 42 U.S.C. § 675(5)(C). See also 42 U.S.C. § 675(5)(F) (definition of the date the child entered foster care), 45 C.F.R. § 1355.20 (definition of the date the child entered foster care).

For a case in which the court determines that reasonable efforts to return the child home are not required due to aggravated circumstances, the permanency hearing must be held within 30 days of disposition. 45 C.F.R. § 1356.21(h)(2). |

State funding stops unless these findings are made. |

|

ENDNOTES

[i] Originally written in 2011 by Sheila Malloy Huber; updated in 2014 by Jennifer S. Meyer; updated in 2017 by Carissa Greenberg

[ii] The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Administration for Children and Families issued National Model Foster Family Home Licensing Standards on February 4, 2019 in Information Memorandum Log No. ACYF-CB-IM-19-01, available here: https://www.acf.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/documents/cb/im1901.pdf

[1] Carissa Greenberg joined the Attorney General’s Office (AGO) in late 2011, after nearly two years in private practice. During her tenure as an Assistant Attorney General, Carissa has served Washington’s public child welfare agency: first, the Department of Social and Health Services Children’s Administration, followed by the newly created Department of Children, Youth, and Families (DCYF). Her experience includes representing the state in dependency and termination cases at the trial and appellate level, and later representing and advising DCYF Headquarters. Carissa is a member of the AGO Academy Committee, which trains all Assistant Attorneys General for the State of Washington. In 2015, she was a recipient of the AGO William V. Tanner Award for outstanding achievement early in her career. She holds Bachelor of Arts degrees in Political Studies and Theatre from Whitworth College (now University) and graduated cum laude from Gonzaga University School of Law where she was a Thomas More Scholar.